A word of warning in advance: this article, the card set, and its accompanying masterclass are partly born out of personal frustration. But don’t worry: I have developed a habit of turning annoyance into productive energy. This is why, first of all, I would like to say thank you to all quick-fix, HiPPO, business and innovation theater, bean-counter, and lip-service managers. Gratitude also goes to all the agile snake oil salesmen and recipe consultants. It was them who “gave me the energy” to devote myself in-depth to the topics below in the first place. Oh, and in the following, I’m referring primarily to our experiences with companies from the D.A.CH region. Here we go:

Innovation is rarely professionally organized and managed

Non-technical innovation is not managed professionally and sustainably in many organizations. What the experts in our network and we at co:dify have observed over the last ten to 15 years is this:

- Executives in charge of innovation are either overwhelmed and insecure, both without being able to admit this publicly, or they come along with a remarkable managerial over-confidence and an entitlement that gives all parties involved the impression that they exactly know what they are doing. However, on closer inspection, we observed that they often are merely lapsing into actionism. In both extremes, there is little understanding of how to practice innovation and internal entrepreneurship, let alone how to anchor it organizationally. Both extreme groups desperately seek answers that can be implemented as quickly as possible. Thus they prefer consultants who promise them off-the-shelf recipes that come “with a guarantee of success.” Alternatively, they copy the same “best practices” that may have already worked more badly than well elsewhere.

- Some large international organizations have already made significant progress in professionalizing their (non-technical) innovation management and have gained experience with agile approaches such as Design Thinking, Lean Startup, Scrum, etc., for more than ten years. The large German “Mittelstand” with 1,000+ employees, in contrast, clearly appears to be a laggard in this respect. Now it slowly wakes up and finds itself in a similar learning process as the corporations ten years earlier. And it promptly and unnecessarily repeats many of the same mistakes the corporates (with their bulging investment pockets) made back then.

- In organizations of all sizes, there is also a persisting belief that “culture” can be directly influenced, e.g., through “mindset change programs” or training. What is missing is the awareness that (innovation) culture can only be influenced indirectly through a parallel co-evolution of both practices and systems.

I could continue this list forever and ponder innovation lab reflexes, capital market- or investor-driven grandstanding innovation theater, or failed attempts to scale Design Thinking, Lean Startup, or Scrum prematurely. But why? Most articles on these topics have already been written. There is even empirical research on much of it by now. This brings me to my next point:

The knowledge is there.

It’s just not equally distributed.

And it is often ignored.

Today, anyone who wants to instill a sustainable, people-centric culture of innovation in their organization is in a much better position than the pioneering companies of 15 years ago. They first had to bring into the world through trial-and-error and experimentation all the frameworks, methodologies, and tools, all the (change) management practices and insights we benefit from today. They left us with puzzle pieces that we could take advantage of if we were smart. Not in a 1:1 copying sense! But as inspiration for an adaptation to our own organizational context. However, to my astonishment, I usually find that this does not happen! Often companies do not even know the innovation practices of their successful direct competitors, not to speak of non-industry pioneer organizations that generously document their practices and experiences and share them with the world.

Why is that so? Why do outstanding product and innovation communities (e.g., InnovationLeader, Innov8rs, HPI + HPI Academy, Innovation Roundtable, Mind the Product, etc.), where lively exchanges about the abovementioned take place, remain unknown to many innovation managers? Why are there management, product, and innovation thinkers who do important synthesis work and bring together the puzzle pieces and experiences of their customers and their own innovation practice, of whose concepts, to our astonishment, companies have still not heard (e.g., the partner team of Innosight, Strategyzer and ChangeLogic; Steve Blank, Rita McGrath, Dan Toma, Esther Gons, Frank Matthes & Ralph-Christian Ohr, John Cutler, and Marty Cagan, to name a few who have strongly influenced our thinking at co:dify)? And if, in rare cases, they have heard of them and use their methods and frameworks, why do they employ them only in a very superficial sense?

Our well-meaning perspective on this is: The hectic pace and unproductively absorbed time for, e.g., politics and stakeholder management that is common in large organizations do not leave sufficient time for many managers and professionals with innovation responsibilities to read, reflect, learn or simply follow the “right people” away from their consultant and industry bubble. In smaller organizations, the concurrence of day-to-day business and innovation work, combined with a thinner capital base, leaves little room to stay up to date. A more cynical perspective on the phenomenon would be: Innovation is just not important enough in some organizations to deal with it thoroughly. People responsible for it only do what is necessary to advance their careers or show on the public side (to investors, politics, the labor market, etc.) that “something gets done” – innovation theater in its purest form.

For us at co:dify and me in particular, such circumstances are untenable – especially in light of the massive challenges and tectonic shifts in our industries that we are facing in Germany and Europe. We by now have learned to recognize CEOs and executives who try to sit out change and transformation until retirement or “pass it on” to their successors. We try to ignore them. But for those leaders and innovators who are truly serious about transforming their organization, we at co:dify strive to help them professionalize as efficiently as possible, in as short a time as possible, and as deeply as necessary, against the backdrop of all the constraints mentioned above. Part of this professionalization is to engage with the ideas and experiences of the abovementioned management thinkers and pioneering organizations in a substantiated way.

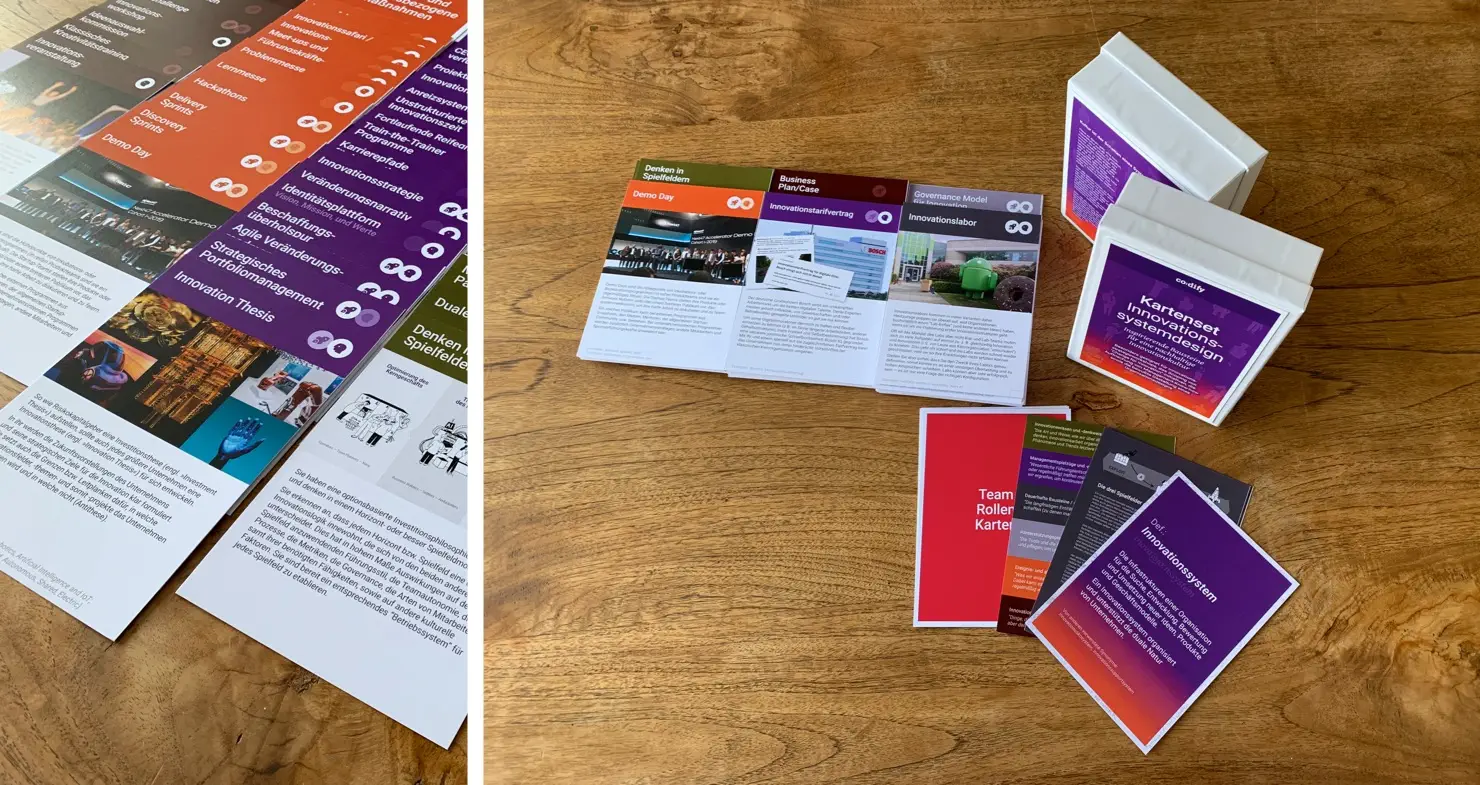

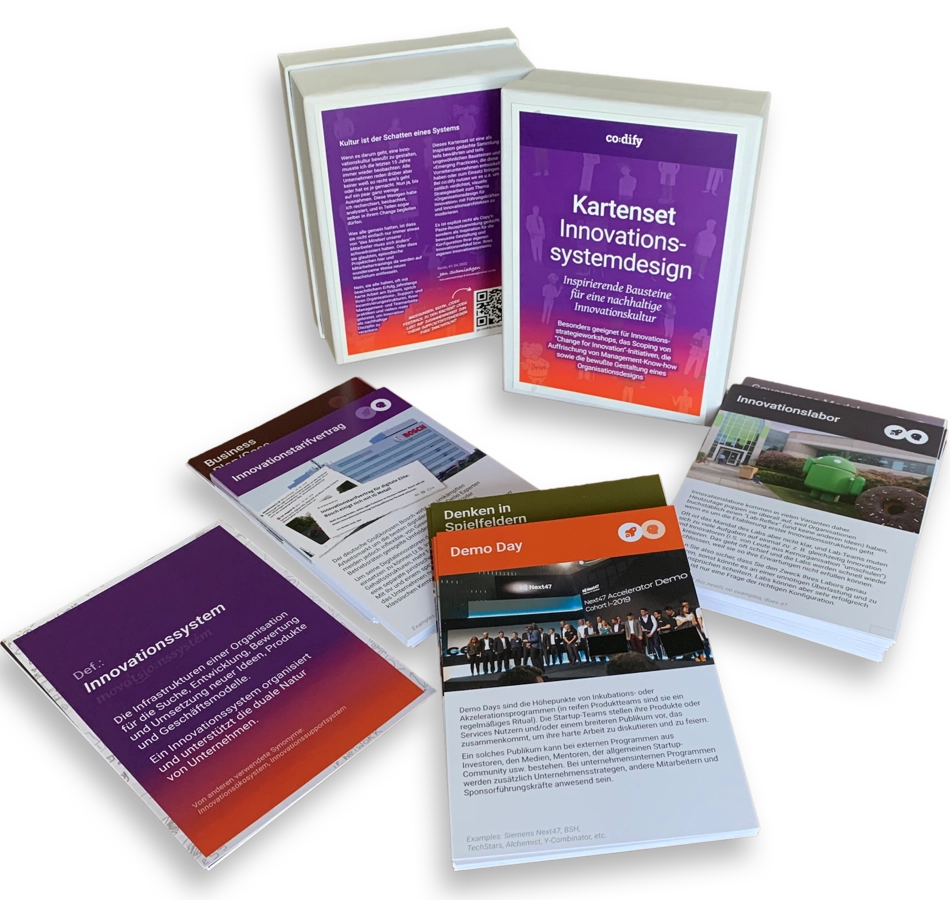

For this reason, I experimented with condensed learning experiences in recent years, in which I gave aforementioned innovation leaders and professionals a Powers-of-Ten-like overview on the topic of “how to arrive at a culture of innovation” via the deliberate design of support structures, i.e. an innovation (eco)system. In these formats, I have experimented with different ways of visually mapping out systems and organizational designs. Out of this work, a visualization in the form of a card set that contains well-functioning, context-agnostic building blocks for establishing an innovation system has emerged. My inspiration for this was card sets like Doblin’s “Innovation Tactics Cards” or Luma’s “Human-Centered Design Planning Cards,” which we enjoy using with our clients every now and then.

First, the overview, then the comprehension

What the card set consists of, and what it does

Although the card set is part of a more extensive learning experience, our multi-day Innovation System Design Course, I realized that it could also be of great value on its own in short sessions as it helps to trigger and moderate valuable reflections on one’s own systemic innovation management. The set consists of six simple categories that Ingo Rauth and I originally developed as an author’s template for a book project. The collection includes 120 cards (as of May 2022).

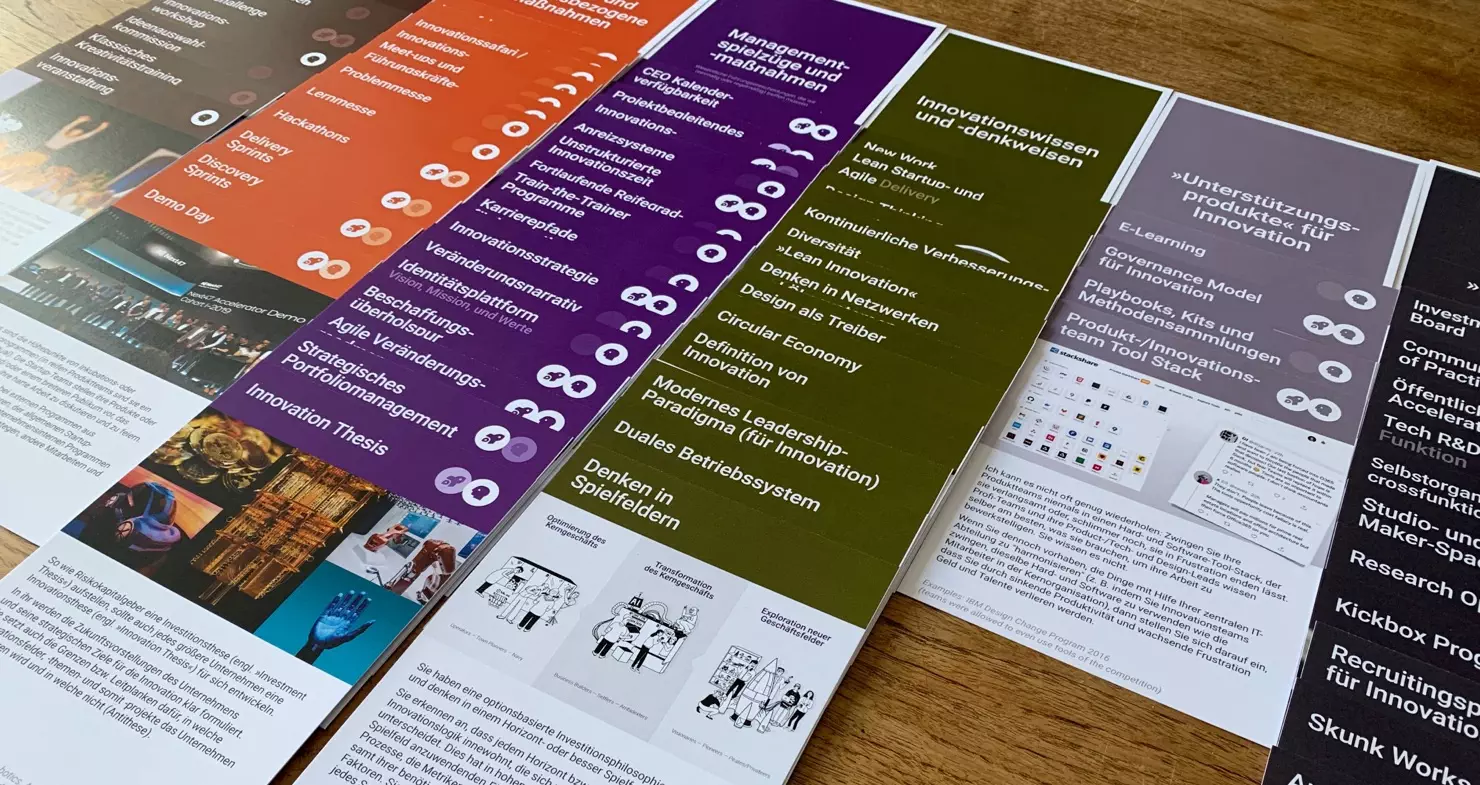

The Categories:

Innovation knowledge and thinking: “The way we think about the (business) world, organize innovation work, and what phenomena and trends will influence the latter.”

Management moves and actions: “Key management decisions we need to make (once or regularly) and actions we take to foster innovation continuously.”

Permanent Building Blocks / “Innovation Vehicles”: The long-term entities we create (which you can go to or talk to) in our organizational design.”

“Support products” for innovation: “The tools and governance documents we create and maintain to support our innovators,”

Event- and activity-based measures: “What we do on an event-by-event basis to innovate. These can be one-time, episodic, or regularly recurring activities.”

Innovation Bad Practice: “Things that rarely work but are common practice.”

I kept the wording of the categories deliberately simple, as we have noticed that many practitioners (at least in the organizations we work with) are uncomfortable with the technical terms used in international innovation research and practice. This simplification may make for less definiteness of some of the vehicles in the card set, but I am happy to accept this for the time being.

All the innovation vehicles and measures in the set exist in different variations in actual, international pioneering companies. In the past, I often received feedback in workshops that what I was presenting appeared to be “academic.” It took me years to understand that this translated to “I can’t believe there are companies out there that have created such an elaborate innovation environment. This is beyond my imagination (particularly in light of what I’ve been experiencing in my organization).” Hence the reminder: none of this is contrived or just a concept. It all comes from lived practice. My sources of inspiration for each of the cards were our own research in the HPDTR program at HPI (where we observed the innovation practice of vanguards like Autodesk, Intuit, IBM, and many more), our own consulting engagements, and coachings, exchanges in international innovation communities, papers and books, and, quite simply, the product and innovation thought leaders from my Twitter and LinkedIn feeds.

Before I describe what you can do with the collection, I’d like to say a few words about what drives us at co:dify and me in particular: We want to increase innovation literacy in the (European) industry and help further professionalize the field. This includes building visual sensemaking and facilitation tools: Everything that helps to get away from long PowerPoint karaoke, abstract biz buzzword bingo, and especially computer screens. So the card form was just a logical consequence of this effort. As a workshop facilitator, you can use it to map out innovation ecosystems in different visualization forms (as a network, as a process, like a pipeline, etc.). It also helps to create conversation starters for those building blocks that the participants are interested in detail or that are relevant to their organization.

Specifically for strategy work with innovation leaders, I wanted the set to have the following effects: It should inspire them and demonstrate the clever ways pioneering companies have identified to organize their innovation activities in a disciplined manner. It should show connections and thus sharpen the holistic view of the “value stream” of (radical/transformative) innovation activities and their interdependencies. It should whet the appetite for zooming in and delving deeper into the functioning of the vehicles before, for example, many millions of euros get wasted in another “lab reflex.” In the best case, the realization may arise that it might be worthwhile to follow the motto: “If you don’t have much time, take more of it at the beginning.” But the most crucial effect I wanted to achieve is this: The set should help reverse the usual discussions among corporate innovators of all hierarchy levels. In this case, from endless complaining and problem reverberating (Lack of skilled workforce! Wrong people! Mindset! Barriers to innovation! Structure! Immune system!) to constructive approaches and solutions. The table below lists a few more observed phenomena that I hope to counteract with the help of the cards:

| Away from … | Towards … |

|---|---|

| The tendency of management to actionistically copy the innovation vehicles of the (often also clueless) competition or to blindly adopt trends and “proven ways” to organize innovation (Safaris, Design Sprints, Labs, etc.) in the hope that these will have lasting effects. | Expose board members, top executives, and innovation leaders (but also other innovation professionals) to the already existing array of “next practices” and options for organizing innovation that might be more contextually appropriate for them. |

| Strategy work via PowerPoint karaoke and flipchart at large, heavy tables in conference rooms. | Contemporary, condensed strategy work at thematic stations of a so-called “Strategy War Room” with the help of visual facilitation. |

| The prevailing extremes in organizations of either looking for over-simplified three-step recipes or trying to get ready-made monster frameworks installed (SAFe, LeSS, AutoScrum). In both cases: not entering the experimentation and codification work yourself to create a unique own operating system for innovation. | Making complexity discussable in a condensed timeframe without literally losing sight of the big picture and its interrelationships. Motto: As simple as possible, as complex as necessary. All with the goal of making a parallel operating system or an organizational design for innovation, visualizable and thus ready for experimentation and prototyping. |

| Subjugating all internal innovators to a single monster process (NPD, Stage-Gate with “Agile Gating,” etc.). | Consciously designing a reasonable small number of innovation pathways with support structures for each playing field. |

| The often observable phenomenon of an organization-wide call to innovate by top management or the establishment of structures (labs!) without concurrently providing internal innovators with important strategic guidelines (e.g., innovation thesis, innovation strategy, change narrative, etc.) and transparent decision-making and innovation pathways (e.g., metered funding, innovation accounting, bridge to the core business, etc.). | To repeatedly make management aware of the basic strategic building blocks needed so that any kind of innovation capability or vehicle, such as labs, can lead to desired results in the first place. |

| Repeating the same mistakes that others already made ten years ago when setting up their innovation structures and thus burning money that could have been used more wisely. | Make the advantages and disadvantages of innovation vehicles relevant to the context of the organization explicit — even before they are potentially implemented. Clearly identify the jobs-to-be-done, financing, and other configuration variables of vehicles and measures to embed them meaningfully in innovation pathways. |

The steps after a mapping:

More clarity and structured procedure

After one or several moderated sessions with the cards and first zoom-ins on vehicles and measures that were worth looking at in detail (e.g., because they have the potential to be adapted to create value in the context of one’s own organization), the following situations might arise:

Situation 01: Companies that are already advanced in their transformation process

Those companies that have already achieved a certain innovation mastery and set up existing support structures will rather have used the cards to map their status quo and consequently fine-tune those areas where they can still improve. More common and more interesting for us at co:dify, though, is the following situation:

Situation 02: Companies at the start of their transformation

The participant group of decision-makers, transformation experts, innovation architects, etc. will have developed a better understanding of what strategic foundations they need to establish first before they can start establishing or redesigning their innovation system. After all, investments should not simply dissipate, and teams should be able to be truly efficacious. This comprehension process of the group will touch on questions of their own attitude, leadership philosophy, governance, metrics, change narratives, innovation thesis, and many more. Often, the group collectively realizes here that essential homework related to business strategy needs to be done before they can address the building blocks of an innovation strategy (the two are not the same thing!). This realization process prevents them from making third or fourth steps before a first one or even blindly copying an inadequate structure just because “the others in the industry” have done it that way (lab reflex!).

Furthermore, the visualization of types of innovation, playing fields, and innovation paths ensure greater clarity as to what the various people really mean when they talk about innovation. It is not uncommon for a CEO to speak about disruptive and transformative innovation, but they actually mean sustaining or efficiency-focused ones. A vocabulary and more clarity here facilitate the usual negotiation and planning processes in which the group will have to decide: “Where shall we start? With what goal? How will we measure success? etc.” At the same time, the mapping will also ensure that the responsible executives learn to anticipate in advance conceptual breaking points – of, for example, a venture-building process – that typically bog teams down in an innovation pipeline. With this knowledge, they can then make more informed decisions about where structure and expertise need to be built first. I also realized that a mapping and guided discussion with the help of the cards can catalyze understanding and translates the rather abstract language of the new ISO 56002 (Innovation Management System — Guidance) norm into a visual model, which also non-expert decision-makers can understand. By the way: the ISO 56002 has surprised us in a very positive sense as it seems to be very much aligned with the philosophies and schools of thought we subscribe to.

These are just a few examples of learning and reflection outcomes we’ve observed when we brought the cards into use in a facilitated way. So far, we have only applied and tested them on a small scale with clients or in learning experiences. I am therefore inquisitive to see whether and how they can also be beneficial for external innovation experts once we have made them available to the public now that we have made them available to the public.

Are you interested in the card set?

We plan to release the collection in Q4 2022 via Kickstarter. It will then be available for backing or purchase via the website: Innovation System Design. Please feel free to sign up for our newsletter if you are interested. As soon as the cards are public, we will announce this. And don’t worry: we rarely write, and only professionally relevant content if we do.

Update as of May 2023: The cards are published now. You can immediately buy digital versions and support my pragmatic “crowdfunding” for producing a printed version (I decided against an official crowdfunding tool like Kickstarter or IndieGoGo, as both are a nightmare when it comes to handling VAT, invoices, and German tax law). Thus we sell our tools now via a service that acts as our “Merchant of Record” and handles all of this so that we can concentrate on building. Oh, and all proceeds from these sales will go to into the further development of the cards and future tools!

1 Comment

This is great Jan. I love that you are applying innovation (and design) practice to our own approaches.