Initially frugal innovation referred to low-cost new products, methods and designs that have been created for or come out of what is known as the “bottom of the pyramid” or the unserved lower end of the mass-market. Nowadays, frugal innovation is understood as the process of developing products, services and business models that are simple, affordable and

accessible, with the goal of improving lives and creating new markets and opportunities. When former CEO of car-maker Renault, Carlos Goshn, was asked for best practices to enable frugal innovation at a company, he referred to four key takeaways from his frugal journey inside Renault:

- Send your top executives to emerging markets to cultivate the Jugaad (frugal) mindset. Only when experiencing the efficacy of frugal innovation and products first hand, you can get a glimpse of what it means to find opportunity in adversity.

- Create “good enough” products that deliver high value for money.

- Foster healthy rivalry among global R&D teams.

- Tap partners in emerging markets who excel at innovating more with less.

The simplicity of these insights surely do no justice to the journey it took Carlos Goshn and companies like Renault to adopt frugal innovation. Here is a bit of background story for the curious innovation expert that want to know why frugal innovation remains being a good answer to many of our 2023 innovation challenges:

The Logan Story

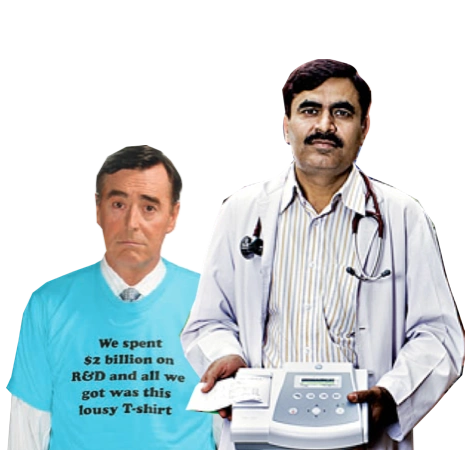

In 1997, former Renault CEO Louis Schweitzer returned from a roundtrip through Russia where he first saw the Lada, a locally made, no-friction car that fulfilled all basic mobility needs at a price tag of only $6.000 – a car that sold considerably better than Renault’s fancier product line. Schweitzer asked himself “why technological progress always comes with higher prices for the customer”. Back in France he requested one of his senior managers and engineers, Jean-Marie Hurtiger, to build the Renault version of a Lada – a car that is modern, reliable, and affordable. Hurtiger soon realized that the task was impossible to carry out with the in-house french design and engineering team that was used to a “bigger is better” mentality with high-quality materials, an abundance of technical features and little limits to the length of development cycles. A mentality that proclaims higher R&D expenditures lead to more innovation – a theme, we like to call “happy engineering” that has already been subject to extensive research.

Hurtiger decided to delegate the task to recently acquired Romanian automotive company Dacia. His assumption was, that by giving the engineering challenge to a team that grew up in a harsh communist environment and combine it with the French designers, it would open up novel ways of product development for Renault. The team began by reframing the simple, but abstract engineering challenge to a concrete technical design brief: Create a vehicle that can carry four adults, a pig, a sink, and 100 kilos of potatoes at a retail price of max. $6.000. Eventually, in 2004, the Dacia Logan was born, a car that took over 40% of the Romanian passenger car market and sold 135,000 times in its second year after launch in Central Europe and paved the way for Renaults low-cost, entry-level products.

Frugal Engineering and Jugaad

When Carlos Goshn succeeded Louis Schweitzer as CEO of Renault in 2005, he built on the strategy of his predecessor by introducing additional entry-models to enrich the Logan product line. Also, he sent senior engineers to Chennai, India to set up a R&D shop that would influence the entry-model platform of Renault for a decade to come. In an attempt to post-rationalize the origin of the Logan, Goshn in 2014 chose the term “frugal engineering” to better describe Renault’s special approach to a R&D and production process in India focusing on the ability to innovate quickly, at low cost, and under severe resource constraints – or in simple words to “do better with less”.

Two years before Carlos Goshn coined the term frugal engineering, it was Navi Radjou, Jaideep Prabhu, and Simone Ahuja who published a book called Jugaad Innovation , that translated the frugal mindset to popular management literature. Radjou, Prabhu, and Ahuja spent four years researching innovation principles throughout India to capture what in Hindi is called jugaad – an innovative fix, hack, or an improvised solution born from ingenuity and cleverness. Jugaad innovations range from clay-made refrigerators that run without electricity to drip irrigation systems with used plastic bottles or the famous dabbawala lunchbox delivery system. For a very recent example, look at Gursaurabh Singh who invented an impressive low-tech conversion kit to turn your bicycle into an e-bike.

In 2016, and soon after Carlos Goshn made frugal engineering a thing at Renault, Navi Radjou and Jaideep Prabhu publish their second book, now called Frugal Innovation . It takes the Jugaad principles and looks for established companies in the US, Europe and Japan who use the principles for their entry into then emerging markets such as Brazil, India, or China. Turns out, Renault was not alone in their approach. Well-known products from General Electric, Philips, or Siemens were fully redesigned for emerging markets, or even developed end-to-end from scratch in an emerging market, and later exported to the US and Europe.

For instance, it was Siemens in 2011 that added a new market segment “M3” to the existing M1 (high price) and M2 (standard) portfolio. The core of Siemens M3 segment was called SMART products. SMART standing for simple, maintenance-friendly, affordable, reliable, and timely-to-market. Siemens’s SMART products were aiming at customers in the M3 market segment who are highly price-sensitive and yet quality-conscious. SMART products were entirely designed and built in emerging markets by Siemens’s local R&D and manufacturing teams, in collaboration with German colleagues. Meanwhile, Siemens’s R&D engineers in India developed micro power grids that can use multiple energy sources — from coconut shells to the sun — to provide electricity to Indian villages with 50 to 100 households. SMART solutions typically were 40 to 60 percent less costly than products designed in Europe or the US.

Innovation fun-fact: Development of the SMART program wasn’t originally conceived at the executive or senior management level, but as a “submarine assignment”, as coined by Armin Bruck, former Siemens India managing director; this refers to the fact that product design occurred in a stealth-like manner without knowledge from headquarters. Local engineers in a factory in Goa, India developed an X-ray machine (Multimobil) on their own that was 40 percent cheaper than its traditional Siemens counterpart. Siemens eventually put its support behind the product and used it as a catalyst to consider a new market approach.

The cost advantage did not come solely from lower wages or lower energy costs, it substantially came from the fact that M3 products were minimalistic and practical in the sense that they solved a core job of the costumer or end-user and neglected many of the perceived “added values” from established Siemens products, e.g. aesthetic high-cost materials, (unnecessary) technical features, or an emphasis on ergonomics.

In an interview 2013, former CEO of Siemens France, Christophe De Maistre, points out that “simplicity and progress go hand-in-hand”. He believed that, in a globalized economy, multinationals must redefine the notion of quality not in terms of technological sophistication, but in terms of value as perceived by a client in a local context. In emerging markets such as China and India, clients want decent quality products that are simple to install, use, and maintain. In the interview De Maistre emphasizes that, “contrary to popular belief, building a simpler product sometimes requires more innovation than creating a complex one — especially in terms of reliability and energy efficiency.“

Lean-by-Force and Key Takeaways

Looking at the last 20 years of experiences with frugal innovation in emerging and established markets and companies, what can we take away in 2023 and beyond? Overall, the key principles of frugal innovation involve a focus on meeting user needs in a simple, affordable, resource-efficient way and a willingness to embrace experimentation and iteration as part of the development process. Some key principles for frugal innovation include:

- Prioritizing user needs: Frugal innovation starts with a deep understanding of the needs and preferences of the target user, and focuses on developing solutions that meet those needs in simple and effective way.

- Maximising value with minimal resources: Frugal innovation seeks to create value with minimal resources, often by using low-cost materials and production methods.

- Leveraging local knowledge and resources: Frugal innovation often involves adapting existing technologies and resources to local context and harnessing local knowledge and expertise to develop solutions.

- Embracing simplicity and minimalism: Frugal innovation often involves simplifying products and services to their essential features, rather than adding unneccessary bells and whistles.

- Being open to experimentation and iteration: Frugal innovation often involves a trial-and-error approach with prototypes and pilot projects being developed and tested in the field before being scaled-up.

Sound familiar? Frugal Innovators are lean-by-nature, or when you apply a more realistic lens, they are lean-by-force. Unlike lean startup thinking, frugal innovation is less intentional than most people might think. So-called western companies tend to apply frugal innovation only in times of economic downturn or financial austerity – which is surprising given that over-engineered products don’t sell better in emerging countries.

In conclusion, the concept of frugal innovation and lean startup share common principles that can greatly benefit us in improving our innovation practice today. Both approaches prioritize user needs, maximize value with minimal resources, leverage local knowledge and resources, embrace simplicity and minimalism, and foster a culture of experimentation and iteration. Frugal innovators are, in essence, lean-by-nature or lean-by-force. The key insight for us is to recognize that frugal innovation is not solely applicable during times of economic downturn or financial austerity, but can be a valuable mindset for driving innovation and creating high-value products and services in emerging markets and beyond.