Design Sprints come in different forms. The most prominent one nowadays is the four to five day Design Sprint codified by Google Ventures’ John Zeratsky, Jake Knapp, and Braden Kowitz . The process is very well elaborated, heavily documented and novice friendly. So, taken with a pinch of salt, we can really recommend their Design Sprint style for appropriate problem contexts. But its main strength — its rigorous codification — is also its weakness. Pushed by toolheads and consultants it unfortunately gets mindlessly applied to all types of problem areas in its highly prescriptive original form. And this is where it breaks. An expert design or innovation team will not use a ‘standard sprint form’ but shape its own design process and sprint cadence.

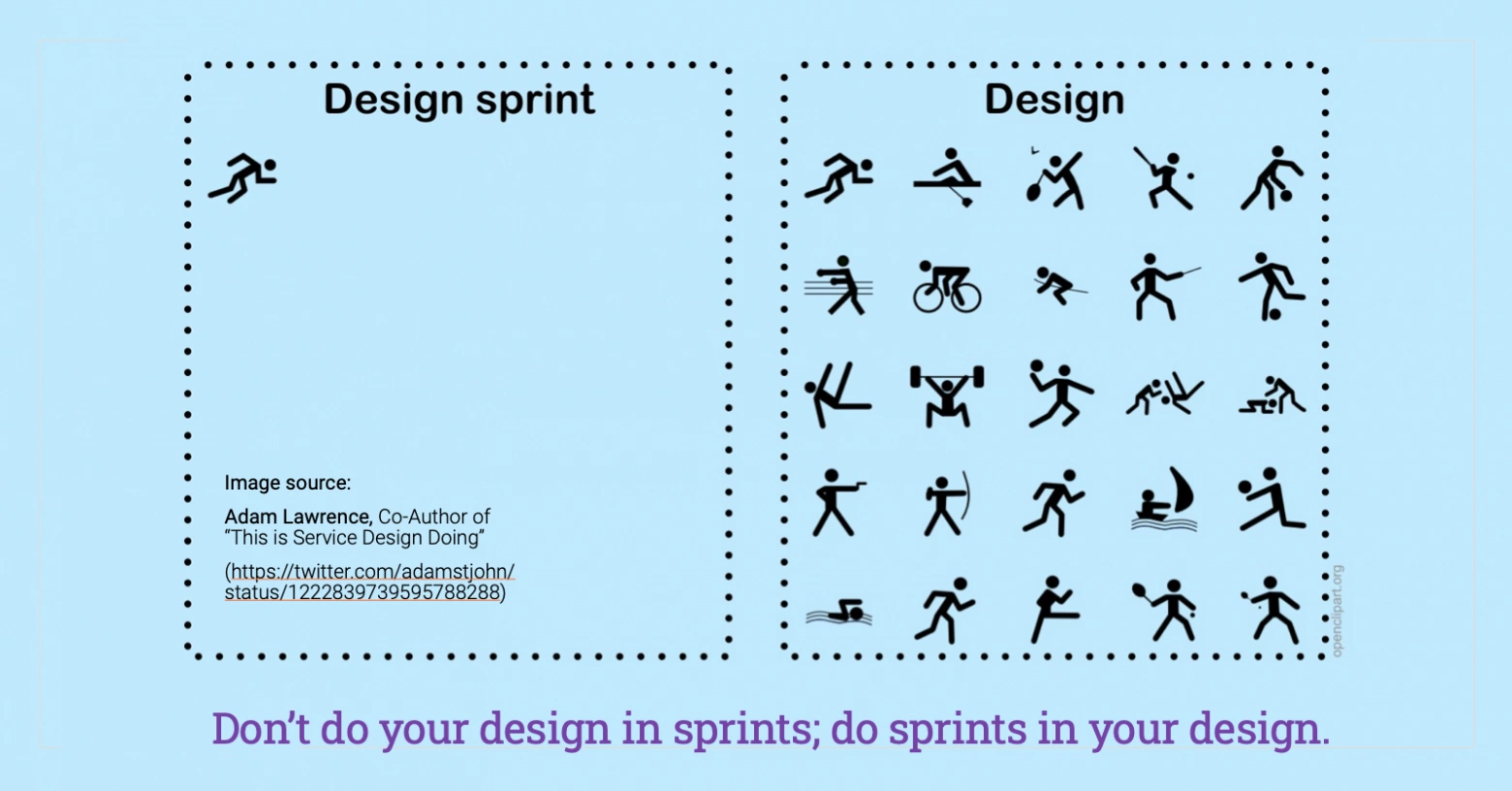

This is why design sprints with slightly different (read: customized) structures already existed before Google Ventures’ made them so popular (e.g. classic ‘fast forward’ sprints, makeathons, research sprints, etc.). In fact, any design and innovation team that needs to structure its work in an ‘agile way’ uses sprints all the time (think of Scrum teams, too). So sprints are nothing less than a way of organizing extensive project work into small batches for a fast cycle-time in learning and delivery. An agile (design) project, therefore, consists of several sprints with differing lengths and foci. This brings us to another widespread misunderstanding worth mentioning: you don’t run a sprint and come out with a ready-made high-fidelity prototype or solution. This is what many project sponsors wish for, but the truth is you ‘only’ develop a critical increment and even crucially a shared understanding in your sprint team, which will advance your project. So, “don’t do your design in sprints; do sprints in your (project) design” (Lawrence A., 2019).