Extract assumptions and visualize them visibly

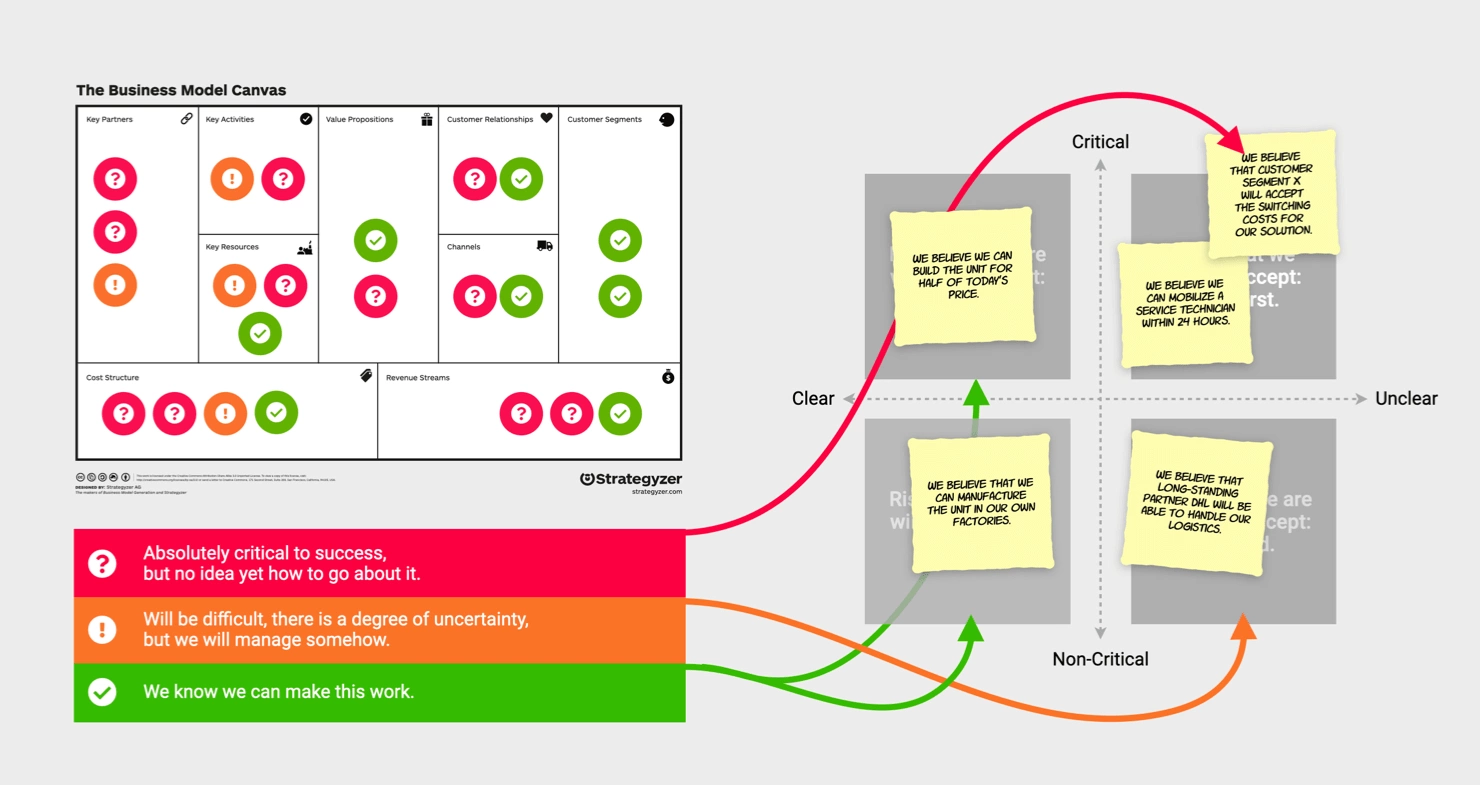

This is the point in my Lean Startup article series where Alexander Osterwalder and his fellow forethinkers at Strategyzer take the stage. They have created quasi-industry standards for the conceptual description of a business model with their Business Model Canvas (BMC) and Value Proposition Canvas (VPC) . Both are world-renowned, widely used and well-documented. I will, therefore, not elaborate on them here. However, they play a critical role in externalizing and making discussable our business model and value proposition scenarios. Indeed, what our Lean Startup team will do is: take those VPC and BMC that they have agreed are most promising and that they want to test. Then extract those critical assumptions from each building block that are so critical that if they were ‘not true,’ they would implode the whole business model scenario. This step is called Assumption Mapping and is wonderfully documented in its detailed steps by David Bland (click here).

By the way, Lean Startup teams have fine antennae for when a team member argues with a shaky assumption based only on their worldview. Because then the person won’t say, “I have data here and am highly confident that #assumption is true/will work,” but will say, “Well, I believe yes that …”. Since every other team member can “believe” something else and it is difficult to build a business model on this, Edwards Deming’s motto applies in Lean Startup teams: “In god we trust, everybody else bring data.”

Risky assumptions first!

The permanent visualization and prioritization of assumptions.

This briefly answers the first question: where do assumptions come from; how do you make them visible; and how do you prioritize them?

Form hypotheses, design, conduct, and measure experiments.

The next step is hypothesis generation. Let’s say the team picks the three to five most critical assumptions and considers how to test them. Depending on the character and question behind the assumption, it will choose a more opening (generative) or closing (evaluative) experimental design. In the latter case, disciplined hypothesis generation is particularly important.

Let’s take a look at a historical Lean Startup example for a so-called channel test: Imagine you are in 1999. You are Nick Swinmurn, the founder of Zappos in the early days of Internet shopping. Crazy as it may sound, probably the riskiest assumption for Nick (and, more importantly, his investors he was trying to get on board) at the time was “People will buy shoes online.” There simply wasn’t anything like that yet, and it wasn’t clear if there would be customers willing to take the ‘risk’ of buying shoes without trying them on and being able to look live.

So Nick’s ‘make-or-break’ assumption was, “We think people will buy shoes online.”

Remember: in Lean Startup, 90% of the time, it’s about measuring actual human behavior. 99% of all companies would now conduct classic market research with questionnaires or focus groups à la “How likely is it that they would order shoes online?” We can’t go into why classic MaFo doesn’t work for such questions in this series of articles because this is a complex topic in itself. That’s why we’ll leave it at this simplified insertion: In Lean Startup, focus groups and MaFo questionnaires are the last resort – usually, they are avoided altogether because experience shows that they don’t work!

But how did Nick go about it without building Zappos from scratch? It’s simple: He photographed popular shoe models, put them on an initial test website, promoted it on Google, and saw if people ordered. When an order came in, he went to the shoe store in person, bought the pair, and sent it to his customer. So, with little effort, he was able to test whether his assumption was right or wrong.

Nick would probably never have talked about testing a hypothesis. It’s just been his natural and intuitive action to get ahead. And it is this very action of real entrepreneurs that Steve Blank, Bob Dorf and later Eric Ries , observed over years, codified afterward and put into a language that can be learned by us corporate innovators. Translated into a post-rationalized hypothesis in terms of the Lean Startup approach, Nick’s experiment design would look like this:

| For this, we measure: … | will result in the following: … | For this we measure: … | We know we have been successful when … |

|---|---|---|---|

| … a ‘Pretend-to-Own’ test in which users acquired via Google AdWords buy shoes online from a facade webstore … | We will sell shoes online. | The click-through rate (CTR) in search engines, inbound traffic, and the corresponding conversion rate of sales on the test website. | For this, we measure: … |

| [Experiment] | [Outcome]. | [Metric]. | … both our CTR and conversion rate are at least 10% (today, more like 1%, but it was 1999!).* |

So, let’s summarize again. The Lean Entrepreneur will, whether consciously or unconsciously, turn his assumptions into structured hypotheses that come with a success metric (usually to measure human behavior). To measure this, he considers a suitable experiment design and a prediction/threshold value to his metric at which his experiment should be considered “successful or invalidated.” Then, according to his time budget, he sets a time period for the experiment to run, analyzes the data/results, and decides his next steps. So he remains in the Build-Measure-Learn Loop until he has reached a certain saturation in his Assumption-to-Knowledge Ratio and can leave the Lean Startup learning cycle because he has achieved Problem-Solution, Product-Market, and Business Model Fit. Or, more simply, when he is confident enough that his former blind spots have been uncovered and he has received enough signals from the market that this business can work and that it is worth building the product “right.”

Thus, we would have briefly answered the questions of how to formulate a hypothesis from an assumption and how to test it via experiments.

Experiment Design — Creativity Meets Analytics

The last open question remains: Where do the ideas for the designs of such in-market experiments come from? The answer is: There are no limits to creativity. This is exactly where the creative founder and lean entrepreneur differs from the MBA or manager operating according to a strategy recipe book. The former will always find unusual ways to get signals from the market so that they can manage their scarce resources (see the examples in Table). The latter once had deeper pockets and tries to minimize their risks with expensive market research, externally commissioned studies, and old-school strategy tools mentioned at the beginning. In our experience, the lean entrepreneur always wins in the context of high uncertainty and entering new markets. However, progressive large companies have recognized this and are trying to practice this way of working more, especially as part of their digitization initiatives. They benefit from the fact that experiment design best practices have emerged for certain issues – especially in digital business models.

Examples of Creative Experiment Designs

| Test Dimension: What question(s) should the Experiment answer? | Exemplary Experiment Designs: What is often used here in practice? | Current and Historical Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Is this a problem, worth solving? | Problem Interviews, Landing Pages, Crowdfunding | Avenir Telecom, Energizer P18K Pop (2019): Is the world ready to use an 18,000 mAh smartphone the size of a brick for not having to charge it for a week? → No, the problem was not big enough. Pebble (2012): Is a critical mass of people ready for a true smartwatch? → Yes. Huge success. |

| Customer Is this customer/buyer group, the right one for our solution? | Problem and Solution Interviews, Email Campaigns, Landing Pages, Mock Sales | Kutol, PlayDoh (1950s): No one cared about Kutol’s wallpaper cleaner. Until the McVicker brothers made a “customer discovery” in the best sense of the word: Teachers, families, and children repurposed the product as play dough. Stewart Butterfield’s pivot from Game Neverending to Flickr (2004): Could we use the front end and functionality of our (unsuccessful) game with its popular photo uploader to build a service where people could interact with photos in real-time? → 2008 Sale to Yahoo. Lego Night Mode (2020): Anyone who took a box of this new series to the checkout at the Lego World store was in for a surprise: they were part of a mock-sale experiment in which the appeal of this series was tested with real customers. He couldn’t buy it yet, because it didn’t even exist yet. But Lego learned which customer segment the series resonates with most. |

| Solution Is our value proposition attractive enough to replace our customers’ or buyers’ current alternative solutions? | Spec Sheets, Landing Pages, Crowdfunding, etc. | James Watt’s Steam Engine Value Proposition Test (1776): Will horsepower resonate with mine owners as a customer-driven metric? And can I convince those with a performance-based business model to adopt the new technology? GE, Fuel Cells (2014): How can we test the attractiveness of our targeted solution without already having to build a complete pilot/technical prototype of a machine? → Data sheet experiment. Joel Gascoigne, Buffer (2010): Is it just my need, or do other people need dedicated “queue tweets” software? Would it be worth building such a tool? → Yes! Overwhelming response. |

| Features How exactly should our solution be configured and presented? | Co-Creation Sessions, Multivariate or A/B Testing, Fake Door Tests, etc. | Lufthansa iHub Mission Control MVP (2018): What tasks will our users assign us or our chatbot planned for the future, with? Can we map this profitably? → Pivot GE, Fuel Cells Pilot Plant + Pilot Customer Testing (2014): Are we technically capable of producing solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) at scale? What does it take to run them profitably at (pilot) customers? What can we learn with them? Fredrik Garneij, Ericsson, “IPv4 as a Service” Proof-of-Concept (2016): An example of a lean experiment that was not deliberately set up by the organization (on the contrary), but wonderfully carries the spirit of low-cost experimentation to test technical feasibility and internal organizational acceptance. |

| Business model How do we ensure that we can deliver the solution efficiently, at scale, and profitably? | Wizard of Oz and Concierge MVPs, Technical PoC Experiments and Pilots, Process Changeover Experiments, etc. | Lufthansa iHub Mission Control MVP (2018): What tasks will our users assign us or our chatbot planned for the future with? Can we map this profitably? → Pivot GE, Fuel Cells Pilot Plant + Pilot Customer Testing (2014): Are we technically capable of producing solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) at scale? What does it take to run them profitably at (pilot) customers? What can we learn from them? Fredrik Garneij, Ericsson, “IPv4 as a Service” Proof-of-Concept (2016): An example of a lean experiment that was not deliberately set up by the organization (on the contrary) but wonderfully carries the spirit of low-cost experimentation to test technical feasibility and internal organizational acceptance. |

| Pricing Which revenue and pricing model is most attractive, both for customers/buyers and as also for ourselves? | MVP and Solution Interviews, A/B or Split Tests, etc. | Amazon, split testing: In the beginning, the online giant only used this type of pricing optimization for itself. In the meantime, it has also made this option available to its retailers. Crowdfunding and pre-sales: The examples from above, such as Pebble, where customers vote with their credit card, or at GE Fuel Cells, where pricing can be tested as a supplement to the data sheet with letters of intent, can help clarify pricing. But pre-sales experiments like Tesla’s pre-booking of new models also help test pricing brand acceptance. |