Put simply, design thinking is the way (industrial) designers have always thought and worked. The term has already been coined in the 60s but got popularized in the mid 2000s by IDEO (David Kelley, Tim Brown), which ran so successful projects for their clients that they asked the innovation and product design firm to teach their way of working to their internal innovators. Together with people from Stanford Mechanical Engineering (Larry Leifer, Bernie Roth, Terry Winograd to name but a few) and the financial support of SAP founder Hasso Plattner they set up the ‘d.School Stanford,’ which codified design thinking as a practice into education programs that have become a kind of industry standard for teaching the methodology across the world. Ever since then design thinking has become synonymous with an innovator’s mindset, as well as a set of behaviors and procedures that can also be acquired and used in daily work by non-designers (a promise that is criticized heavily).

Today it often gets defined as a team-based methodology to the creation of user-centric innovation concepts. The reason why it resonates with digital technology firms (in spe) in particular is that it encourages people to think solution-free and discover latent needs from a human-centric perspective by co-creating with users. And all that before even thinking about technology and business model aspects. It therefore de-risks the biggest threat to any digital and non-digital venture early on: the ‘Market Risk’.

The Popular Notion

In the current industry discourse three aspects of design thinking — in terms of ‘ingredients for success’ — are emphasized: 1) people (multi-disciplinary teams), 2) process (the iterative and agile way of working), and 3) space (‘psychological safety’ and physical space as a facilitator of the teamwork). We acknowledge the importance of these dimensions but regard them as too simplistic to describe what design thinking’s elements are. We also don’t want to go into detail about the different meanings it can have in the different academic and practitioner discourses.

Our Notion

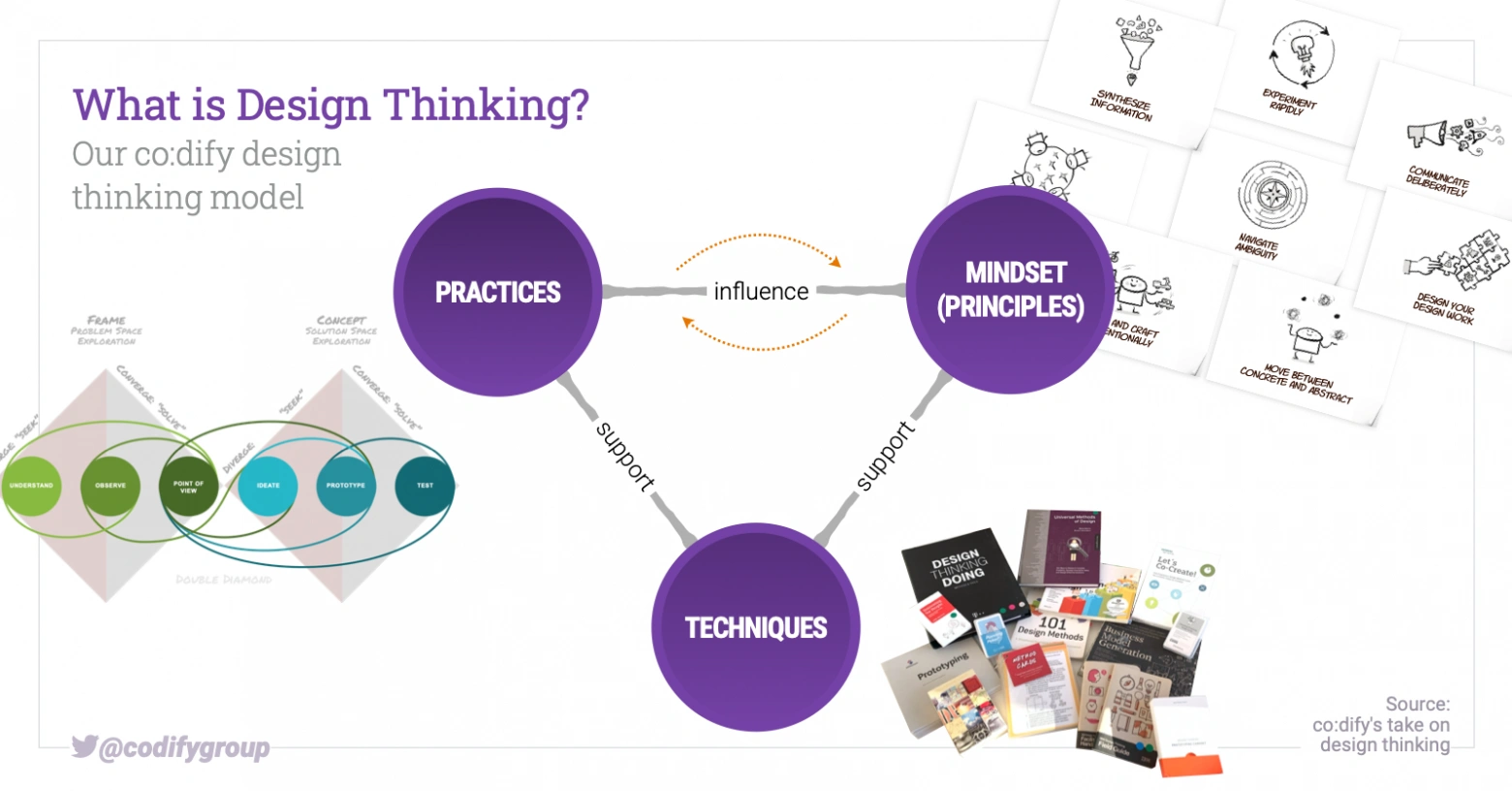

When we support the introduction’ of design thinking in organizations new to the topic, we use a general explanation framework, which is methodology-agnostic and can also be used to explain Lean Startup and other approaches. It describes interoperation of three dimensions: guiding principles (which taken together can form the arcane design thinking ‘mindset’), daily common practices, and the use of design and innovation techniques. For design thinking they can briefly be explained like this:

Practices

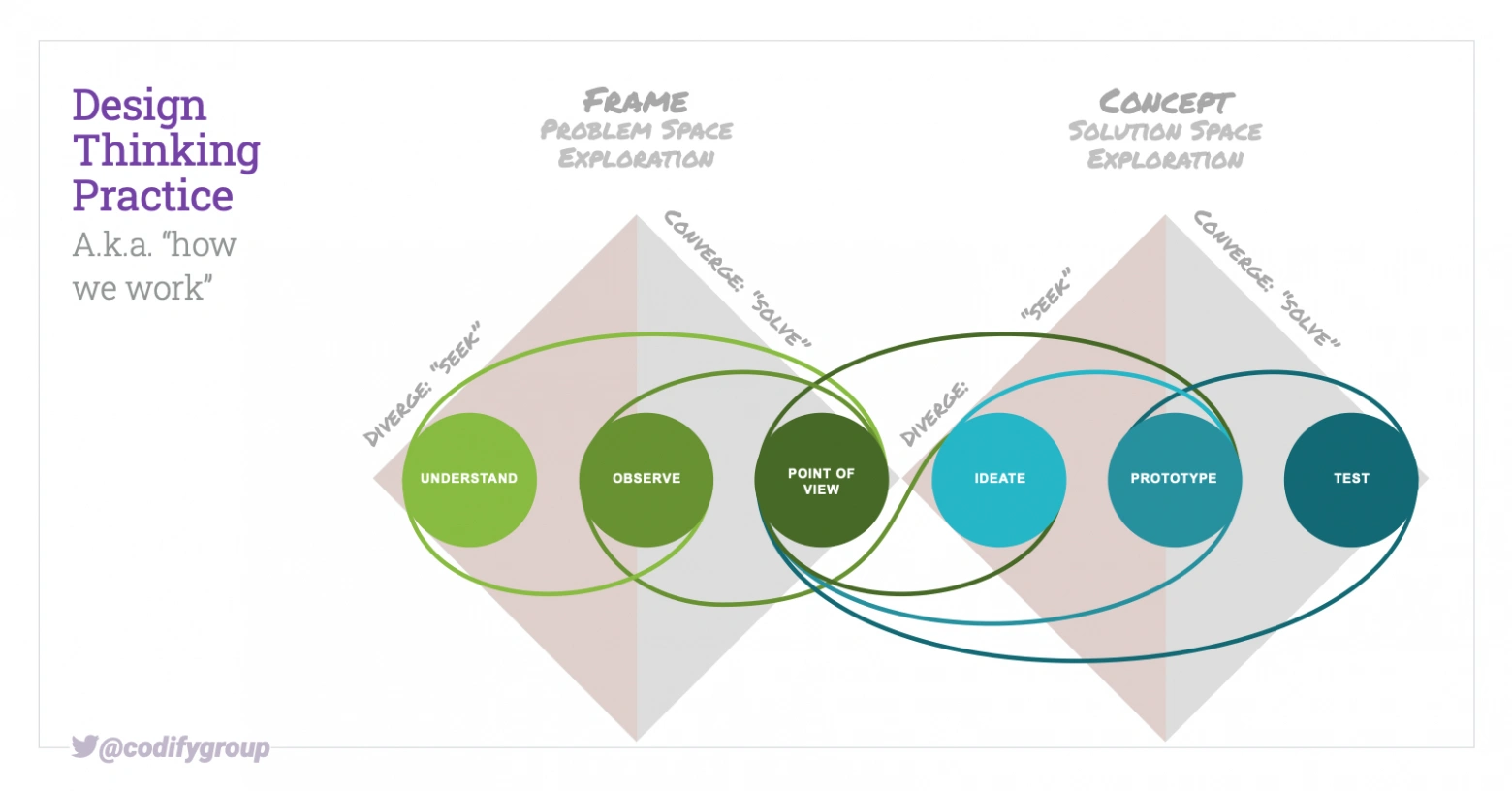

Practices describe the way, how people in a design-minded organization work. But not only regarding process but also how leadership organizes their teams’ daily work in terms of a governance structure and management system (e.g., mandatory integration of sponsor users in every project, agile feedback loops, solution-free design challenges, conscious use of space, etc.). They are therefore heavily linked to the principles and the belief system the organization and its people follow.

An entrepreneurially inclined person, for example, will work iteratively and by experiment without even thinking about it. A person with a social sciences background will always integrate users in his development work. A designer will visualize and prototype by nature. As a design thinking organization in the making, you might want to permanently integrate the working methodologies of people from all disciplines such as the ones mentioned.

In design thinking we borrow and remix a lot from other disciplines, to balance out the biases and ‘professional damages’, our own professions and grown belief systems have brought upon us. Gradually and over time the new practices might complement or overwrite our old waterfall-ish operating system for (the fuzzy front end of) innovation.

Examples where design thinking inherited and borrows from other domains:

Ethnographic Research Processes, SCRUM Sprint Cycles, CPS (Creative Problem Solving) Practices, etc.

Governance structure examples:

IBM’s ‘Hallmark Program’, Intuit’s ‘Design for Delight Program’, Bosch’s ‘Team Bonus Model’

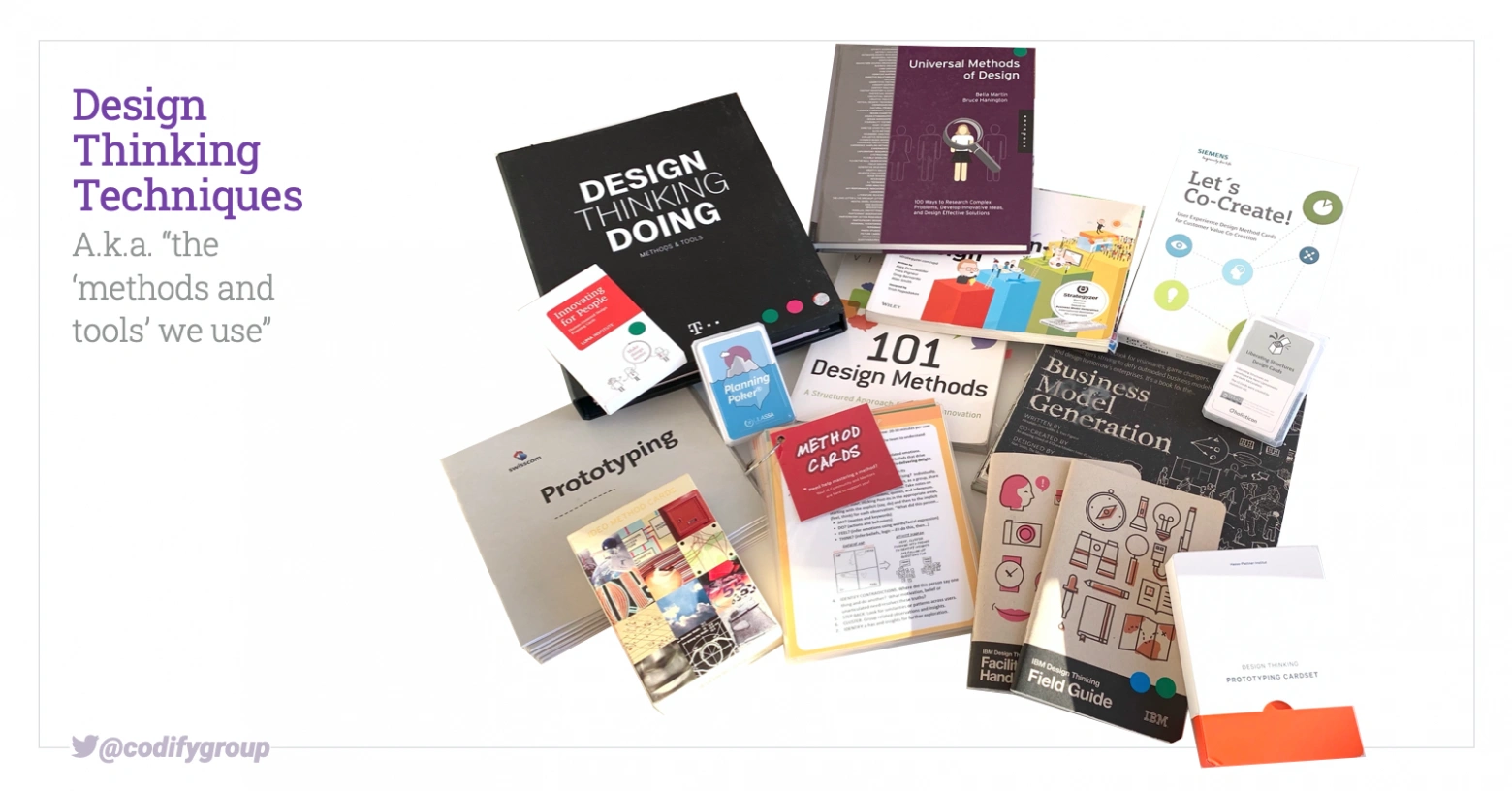

Techniques

Techniques are ways of carrying out particular tasks. In corporate lingo, we usually call them methods and tools. Just think of the ‘Balanced Scorecard,’ the ‘Business Model Canvas’, or a ‘Customer Journey Map’.

Design techniques support practices and the development of a design mindset. We ‘steal,’ borrow, and remix those tools and methods from other professional domains that help us exercise our practices more worthwhile and efficiently. Some of them need years of training, others can be applied by everyone right away. Yet, we should always be aware: it’s the ‘soft skills’ that often are hard to acquire!

Example Techniques:

- Design Ethnography: Cultural Probes, Participant Observation

- Synthesis: Empathy Map, Persona, Ecosystem/Stakeholder Map

- Rule-based Brainstorming and Creativity Techniques: Disney Method, Six Thinking Hats, Pain-Storming

- Service Prototyping: User Journey Mapping, Service Blueprint, Body-Storming

- Business Design: Value Proposition and Business Model Canvas, Value Flow Mapping, Lego Serious Play

- Decision-Making: Forced Ranking, Dotmocracy

- Productivity: Kanban Board, Getting Things Done (GTD), Pomodoro

- Feedback: Start-Stop-Keep, I like I wish, Daily Standup

Principles

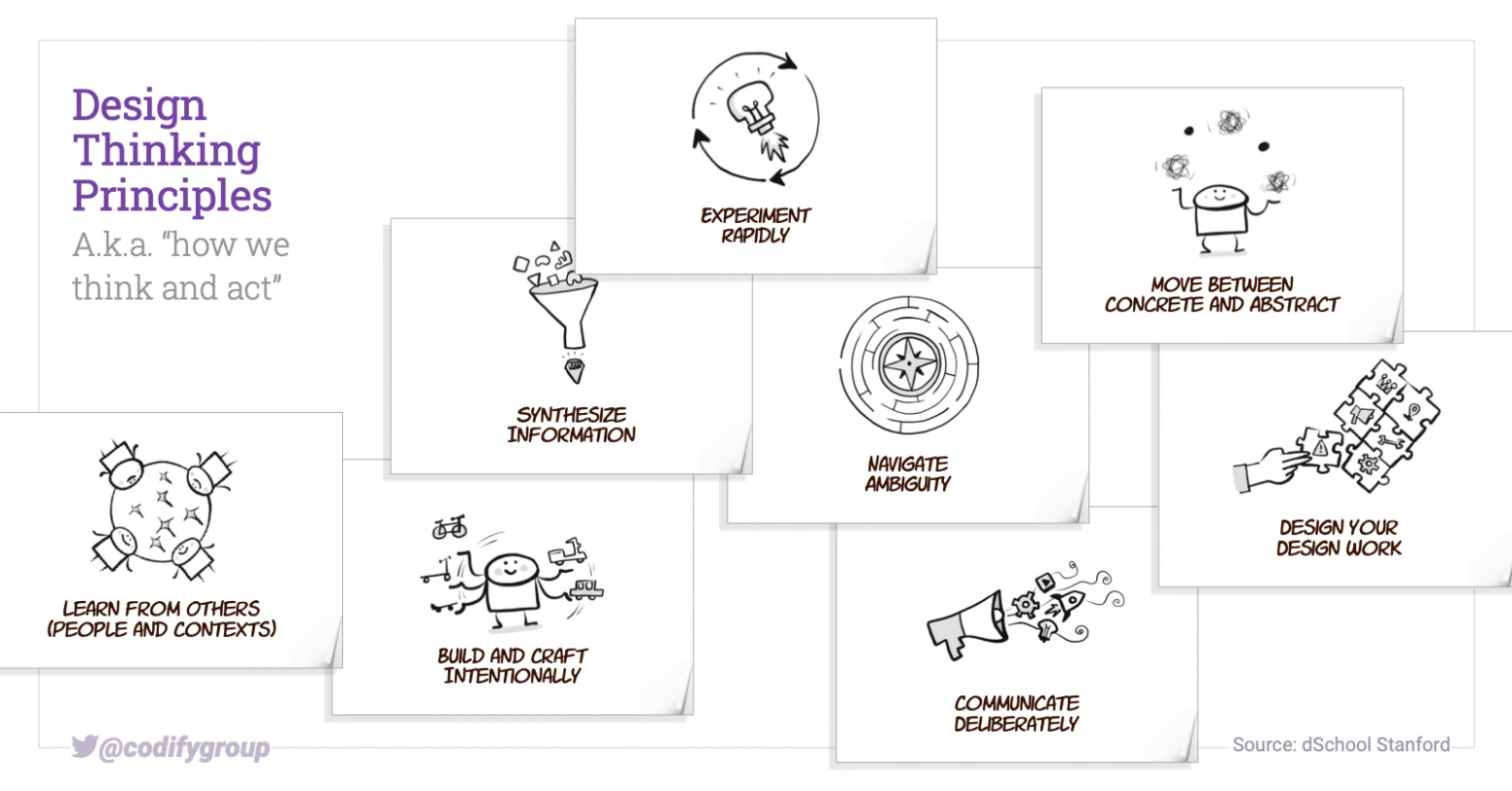

Someone who lives and breathes design thinking has a special way of thinking: It is guided by overarching ‘rules’, attitudes, or beliefs, which we call principles. Taken together they form a mindset. Principles are dual in nature: For those who already live them, they guide all their action. For those who don’t work in this way yet, they serve as an aspiration. But more important principles also imply certain abilities, which are heavily linked to concrete techniques. What does that mean? Well, it takes lots of practice and a certain personality to be skillful at externalizing information (sketching and modeling techniques), to be able to quickly set up experiments (rapid prototyping techniques) , or to really get to the bottom of things with users (question and data triangulation techniques). Therefore principles and techniques usually co-evolve in practice and by training.

An example of how design thinking principles can be formulated as to be learned abilities comes from the d.School Stanford with their eight core abilities. We also use them in our work with clients.

A final remark for our seasoned colleagues from the design thinking expert community: This is the working definition and model we use with non-designers and industry leaders to get started. We are fully aware of the myriad of maturity models, NextD geographies, and whatever you call the emerging practice of next-generation design thinking. Our experience is: many industries are not ready to get introduced to such sophisticated notions yet. We take one step at a time and slowly prepare organizations to incorporate at least classic product/service design thinking. And we do so by using organizations/systems design thinking with the change agents and leaders we work with. That’s as advanced as it gets. Discussions about higher-level design thinking we happily leave to the various Reddit, LinkedIn, and other community groups.